- „(…) Credit Suisse strategist Andrew Garthwaite (…) writes that ‘to us, China remains the biggest macro risk currently. We would expect aggregate demand to continue to slow (owing to a slowdown in housing, manufacturing investment and exports and there needs to be a destocking) but we also would expect to see an accelerating policy response which should be enough to stabilize PMIs at lower levels’.“ – Stelter: Natürlich, die chinesische Regierung wird, wie ihre Vorbilder im Westen, alles daran setzen, kurzfristige Schmerzen zu verhindern – egal, was dies für langfristige Konsequenzen hat.

- „And while the ‘house view’ from the Swiss bank is that the Chinese government still has policy flexibility and none of the preconditions for a hard landing are currently present, it does caution that as one of its biggest possible outlier surprises for 2019 that, China suffers a hard landing, defined as real GDP growth slowing to sub 5%. So is a China hard landing probable in 2019, and how could we get to that point? Credit Suisse lays out several key developments that could get us there, starting with aggregate demand growth, measured as the sum of exports, FAI and retail sales, is at the weakest in 20 years.“ – Stelter: Die Nachfrage ist so entscheidend.

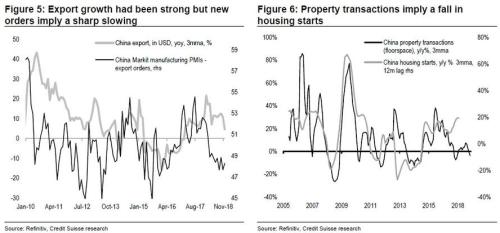

- „(…) the key drivers of demand are likely to continue to slow: Exports have been front loaded and new orders suggest export growth continues to fall. Housing starts are expected to fall around 8% in 2019 (…) with the fall in property transactions and the end of shantytown loans.“ – Stelter: Und da muss man im Hinterkopf haben, dass der Unternehmenssektor in China unter hohen Schulden leidet:

- „(…) manufacturing investment could slow sharply to reflect the fall in corporate profits, coupled with an inventory destock: inventories are in the top 10% of their range, with NBS PMI new orders vs inventories now at their lowest level in their five-year history.“ – Stelter: Typische Symptome einer Abschwächung.

- „(…) China’s housing sector ‘seems the most likely catalyst’ because if we look at the credit bubbles in Spain, Ireland, Japan or the US, then ‘the recession occurred soon after house prices started to fall.’ Consider this: China has seen the fourth biggest increase in credit to GDP of any economy over a 10-year period; this is notable because all the other countries that have seen a larger increase in leverage ended up with major recessions (Ireland, Spain and Thailand).“ – Stelter: Ich habe diese Geschichte schon vor drei Jahren anlässlich einer Konferenz in China erzählt. Und was ist passiert? Nichts. Damit will ich nicht sagen, dass es keine Rolle spielt. Wir haben es aber mit einer sehr leistungsfähigen Regierung zu tun, die zudem über erhebliche Verschuldungskapazität verfügt.

- „(…) much of this credit excess has gone into real estate (…) in China real estate is as high as a proportion of GDP, and two measures of affordability look clearly stretched: rental yields are one third of the mortgage rate (a simple measure of affordability) and the house price to wage ratio is among the highest in the world.“ – Stelter: Dem steht entgegen, dass das Land natürlich erst die Kapazität für Wohnen schaffen muss, bevor die Menschen vom Land in die Stadt ziehen.

Quelle: Credit Suisse

„CS thinks that property is the key to a potential hard landing in China as property accounts for 40–50% of banks‘ collateral and around half of household wealth. The worry is that:

- Property turnover is consistent with a small fall in property prices.

- As above, affordability is stretched.

- 29% of Chinese urban households have at least one vacant property.

- The problem with this is that the home ownership rate in China is already very high (c.73% according to analysts‘ estimates), which means should any cracks appear, they will be few potential buyers that could step in (if not the government).“ – Stelter: Ich würde darauf setzen, dass die Regierung eingreift und stabilisiert.

- „Demographics is not helping as well. The working age population has already peaked and the country is rapidly ageing. Rising urbanisation should be supportive, but the Japanese experience makes us less sanguine. Admittedly, it is slow moving and unlikely to cause a large price correction in itself.“ – Stelter: Was wiederum ein immer wieder unterschlagener Faktor ist. Die demografische Entwicklung ist gut vorhersagbar, aber wird dennoch verdrängt.

- „China has two key supports for allowing an ‘overvaluation’ of real estate — first, that disposable income is still growing at ~8% (helping to improve affordability over time) and second, there are very few alternative venues for investment in mainland China (with a high saving ratio, capital controls and an underdeveloped financial markets). The Swiss bank also admits that Chinese property developers tend to lead property turnover, which in turn leads property prices. Property developers have recently started to underperform but have held up remarkably well in the past year.“ – Stelter: Was dann stimmt, wenn der Leverage im Bereich der Immobilienfinanzierung nicht so dominant ist. Da wir aber eine steigende Verschuldung sehen, müssen wir es ernst nehmen.

- „The investment share of GDP remains extreme. This is a problem because when GDP moves from being investment-led to consumer-led, the GDP growth rate tends to halve.“ – Stelter: Die Umstellung der Wirtschaft ist eine große Herausforderung und führt immer – historisch betrachtet – zu entsprechenden Umstellungsproblemen.

- „China accounts for 22% of global investment, it is responsible for just 10% of global consumption and thus this excess capacity has to be exported. However, this is now more difficult for both political and economic reasons. The danger is when excess capacity leads to domestic deflation. This pushes up real rates which could in turn trigger a major deleveraging. Both PPI inflation and GDP deflators have dropped significantly recently.“ – Stelter: Und nicht nur in China gäbe es dann Deflation, sondern es wäre ein weltweites Problem. Ein deflationärer Impuls ist das Letzte, was die (hoch verschuldete) Weltwirtschaft gebrauchen kann.

- „Credit Suisse is worried that China’s leadership does too little, too late and that in turns allows the credit bubble to deflate much more aggressively. The risk is that the leadership has a higher ‘pain’ threshold than normal to slowing growth as: (1) with the lifting of the term limit for President Xi, there is less need to focus on short-term boosts to growth, and (2) there is not yet a sharp rise in official unemployment with the job offer to application ratio still high at 1.2 and the urban unemployment rate of 3.8% officially (its lowest level since 2002).“ – Stelter: Den Eindruck habe ich nicht, hat doch die Geldpolitik in China schon auf Expansion geschaltet. Da dies auch politisch bestimmt ist, handelt die Regierung also.

- „The current account fell to a small deficit for the first three quarters of 2018. Indeed, this might mean that the leadership would deem cutting rates and allowing the RMB to depreciate as the most appropriate response — something that would not only export deflation but also potentially cause a protectionist backlash among its trading partners.“ – bto: Weshalb dieser Weg meines Erachtens versperrt ist. In den letzten Tagen hat die chinesische Währung auch aufgewertet.

- „With a consumer share of GDP of 39%, it is obvious that in the long run growth has to be led by the consumer. The problem is that after Norway, China has had a bigger increase in household debt to GDP than any other country. – Stelter: Andererseits gibt es mit der Verschuldung noch Potenzial nach oben.

- „While it may comes as a surprise to some, the debt to disposable income ratio is above that of the US (at 118% versus 104% in the US). The debt service ratio has also increased significantly in recent years, and is likely to increase further given that consumers are incurring more expensive forms of borrowing, i.e. via credit cards or short term loans. Credit card debt to GDP now is about 7%.“ – Stelter: Ja, das überrascht mich wirklich!

- „As a result, Credit Suisse economists argue that growth of nominal disposable income net of debt services (i.e. income available for consumption) has dropped to 2%.“ – Stelter: Damit würden die Konsumenten aber als Stütze der Konjunktur ausfallen. Wenn alles nicht fliegt, also Konsum, Investition und Export. Was dann? Staatliche Konjunkturprogamme. Also noch mehr Investitionen in Bahntechnik etc.

- „According to a paper published by NBER, the financial crises between 1980–2007 resulted in a hit of c7% of GDP on average (admittedly with a relatively large standard deviation of 9%). A 7% hit would push Chinese GDP growth to conventional recession territory.“ – Stelter: Wobei in China der Weg der staatlichen Investitionen und Programme offen ist. Eine Runde können sie damit noch gut bestreiten.

- „(…) the question to ask is whether China has the fiscal flexibility to deal with a banking crisis. The two previous banking crises in China have had NPLs in excess of 20%. If this happened again, then NPLs would be around 30–40% of GDP (as bank loans are c.155% of GDP and total non-government credit to GDP is c.205%). If we assume that two thirds has to be written off, then the cost would be c20-30% of GDP.“ – Stelter: Was nun wiederum keine undenkbare Größenordnung ist.

- With around 23% of local government revenue coming from property/land sales, then the budget deficit could be significantly worse than this.“ – Stelter: Weil es den doppelten Effekt sinkender Einnahmen und steigender Verbindlichkeiten gibt.

- Finally, if we include local government financing vehicles and other off-budget liabilities, total government debt to GDP is at 68%. The number is likely to be much higher once we include debt owed by SOEs, as non-financial corporate debt is at 155% of GDP and, according to ADB, SOEs account for approximately 2/3 of them, i.e. more than 100% of GDP. Thus, China’s fiscal ability to maneuver could be much more limited than would appear to be the case.“ – Stelter: Ich finde es nicht ganz sauber, weil man die Verschuldung der Unternehmen nicht „doppelt rechnen“ sollte. Aber selbst wenn, dann zeigen Länder wie Japan, dass man mit eigener Notenbank viel höhere Schulden stemmen kann.

Klar ist, dass, wenn China wirklich in eine Rezession fallen sollte, dass dies die Wachstumsrate der Weltwirtschaft nachhaltig treffen würde:

- „China has accounted for 36% of the global growth since 2013 and accounts for 16% of the world GDP (on current exchange rates, 18.7% on PPP). If China growth slows to just 4% (i.e. c.2.2% lower than we expect), that would take 0.4p.p growth off global GDP directly. However, the total impact would be about double the size because the foreign trade multiplier is typically 2x to 3x (we assume 2.5x). In other words, if China growth slows, the growth of other Asian countries would likely to slow in response. One can see this beta by looking at the sensitivity of say German exports to China versus China GDP growth (last time when Chinese nominal GDP dropped to 6% in Q3 2015, imports from Germany dropped by c.20%).“ – Stelter: Na ja, das Märchen vom reichen Land endet ja bereits jetzt. Würde das Ganze noch beschleunigen und dramatischer machen.

- „(…) China GDP growth slowing to 4% would take approximately 1% off global GDP growth. Global PMIs are already pointing towards 2.8% global growth and thus global growth could fall to just below 2%. This would be the lowest level since 2009.“ – bto: Und die Zinsen sind schon sehr tief …

- „(…) even this may underestimate the impact because should China slow significantly, it is likely to be accompanied by deflation (i.e. the GDP deflator becomes negative) and thus nominal GDP in China could slow by even more. If the deflator falls from the current 1.5% to ‑1% in this scenario, then nominal GDP in China falls from 9.4% to 3% and this then takes 2% off global nominal GDP growth.“ – Stelter: Was dann negativ wäre bzw. bei null.

- „(…) the biggest problem is that this time around, unlike 2008, the space for policy response is limited (real rates in a recession typically need to be cut 4% to 5%), and there is no new China to take over the leadership of global growth.“ – Stelter: Durch ein billionenschweres Konjunkturprogramm!

→ zerohedge.com: „Seven Reasons Why China Is Facing A Hard Landing In 2019“, 1. Februar 2019

Quelle: tbo