Heute vor einer Woche habe ich das Papier der deutsch-französischen Ökonomen zur Sanierung der Eurozone diskutiert. Nette Ideen ohne jegliche praktische Relevanz. Lösen sie doch keines der wirklichen Probleme der Eurozone.

Dasselbe gilt für die Ideen der GroKo, getrieben von einem Martin Schulz, der sich als Retter Europas sieht, koste es uns, was es wolle. Auch nach seinem Ausscheiden aus der Politik (hoffentlich!) bleibt das Thema Euro mit einem falschen Ansatz im Programm einer Regierung, der es wohl um alles geht, nur nicht um das Land. → Der bevorstehende Meineid der GroKo: Schaden mehren, statt abwehren

Aufgrund meines Werdegangs bevorzuge ich eine gründliche Analyse des Problems, bevor ich eine Lösung vorschlage. Dies sollte unsere Politik auch vornehmen, statt bereitwillig auf die Lösungsvorschläge anderer Länder zu springen, die völlig legitim ihre eigenen Interessen vertreten. Sollten wir halt auch tun.

Was die Probleme der Eurozone sind, kann man zum Beispiel einem neuen Papier des IWF entnehmen. Schauen wir es uns genauer an:

- Zunächst die Erinnerung an die Erwartungen an den Euro: „European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) was expected to foster greater macroeconomic stability, prosperity, and convergence. The introduction of the single currency would stabilize exchange rates and lower interest rates across the union. Policymakers assumed that by eliminating exchange rate uncertainty and reducing cross- border transaction costs, a common currency would increase capital mobility and intra- regional trade, thereby boosting growth and helping per capita income levels to converge between poorer and richer countries.“

– Fazit: Und die entscheidende Frage ist, wurde das Ziel erreicht? - Vordergründig ja, aber eben nur vordergründig: „EMU succeeded in establishing a credible monetary policy framework and deepened financial integration, but many national governments failed to exercise sufficient fiscal discipline and to undertake sufficient structural reforms. In the first decade of the euro, countries benefited from a stability-oriented monetary policy framework with low interest rates, low expected inflation, and a stable, common exchange rate. However, national fiscal policies were pro-cyclical and the structural reform momentum faded, leading to macroeconomic imbalances and widening competitiveness gaps. With weak financial supervision, rapidly increasing cross-border capital flows ultimately served as a destabilizing force.“

– Fazit: und wie. Es kam zu einem massiven Verschuldungsboom, der uns erst in die Krise geführt hat. - „The euro area crisis has tested the stability of the euro area and exposed trends of economic divergence. The euro area is emerging from a deep crisis that has challenged the ability of its macroeconomic policy framework to deliver stability and prosperity. While countries such as Germany are now well above their pre-crisis GDP levels, in other countries such as Italy, GDP is only expected to return to its pre-crisis level in the mid-2020s. In such a weak growth environment, distributional issues become more pressing, which could cause the current widening of real income gaps to threaten the social cohesion of EMU. Moreover, the positive effects of economic union on trade, labor mobility, and productivity have been weaker than expected, while cross-border capital flows materialized, but served as a destabilizing force.“

– Fazit: Im Klartext, der Euro funktioniert nicht und trägt mehr zur Destabilisierung als zur Stabilisierung bei.

An dieser Stelle können diejenigen mit wenig Zeit aufhören zu lesen. Die Ziele wurden nicht erreicht und wenn man an den Zielen festhält, dann muss man andere Dinge tun, als die gestern hier vorgestellten. Man muss das Bankwesen reformieren, man muss Arbeitsmärkte liberalisieren, man muss Konkurse zulassen, man muss in Bildung und Technologie investieren. Eine Menge Themen, die anstrengender sind als der Ruf nach mehr Geld/Umverteilung.

Die Studie des IWF untersucht: „(…) three broad areas of convergence are explored: i) nominal convergence (interest and inflation rates); ii) real convergence (income levels and productivity); and iii) convergence of business cycles and financial cycles. We examine the economic channels expected to facilitate convergence, such as increased trade, capital flows, labor mobility, fiscal harmonization, and increased structural flexibility.“ – Fazit: Und wir schauen uns die Ergebnisse an.

Nominal Convergence

- „Inflation rates converged substantially before euro adoption, but did not align further thereafter. Amid global disinflation trends and in line with the convergence criteria for price stability that countries had to meet to join the euro area, inflation rates in EA-12 countries converged toward the rates in low-inflation countries. (…) Since then, however, inflation rates have not converged much further. (…) in the ensuing years of contraction in these countries, inflation remained close to the euro area average, pointing to structurally higher inflation in these economies.„

– Fazit: Die Inflationskultur hat sich gehalten, trotz der Mitgliedschaft im Euro. Das muss verstehen, wer von einer Rettung der Eurozone träumt.

- „While the variation in inflation rates across euro area countries is relatively small, the persistent inflation differentials contributed to competitiveness gaps. Looking at average inflation rates over 1999–2007, the same countries (Ireland, Greece, Spain, and Portugal) were consistently in the upper end of the inflation distribution (text chart). This persistence of higher inflation led to a progressive deterioration in these countries’ competitiveness over time, as reflected in widening gaps in real effective exchange rates.“

– Fazit: ein Thema, das in den Betrachtungen der deutsch-französischen Ökonomengruppe nicht mal am Rande erwähnt wird. Doch wie sollen die Krisenländer dauerhaft besser werden?

- „As a result, real interest rates fell sharply in some countries and overshot convergence, dropping below Germany’s real rate. With nominal interest rates converging more completely than inflation rates, higher-inflation countries had lower real rates, which in turn fueled credit booms and domestic demand, re-enforcing inflationary pressure. In fact, countries that had previously had real interest rates above Germany’s experienced lower real interest rates than Germany from about 1999.“

– Fazit: was die Schuldenblase befördert hat und damit in die Krise geführt. - „(…) the convergence in interest rates also implicitly meant that markets stopped differentiating credit risk across governments, based on a belief that euro area sovereigns would never default. This effectively undermined governments’ incentives for economic reform to improve productivity and competitiveness. With the financial crisis, markets repriced debt as the differences in credit risk became more apparent. The convergence dynamic thus went into reverse, as the countries with the largest spreads at the time of the Maastricht Treaty experienced the most dramatic increases.“

– Fazit: bevor die EZB mit ihrer Geldpolitik die traumhafte Fehlsteuerung wieder geschaffen hat. - „To summarize, the cumulative effect of small, but persistent inflation differentials and converging nominal interest rates after euro introduction hampered real convergence.“

– Fazit: Und daran ändert sich nichts, wenn man eine Schuldenunion herbeiführt.

Real Convergence: Income and Productivity

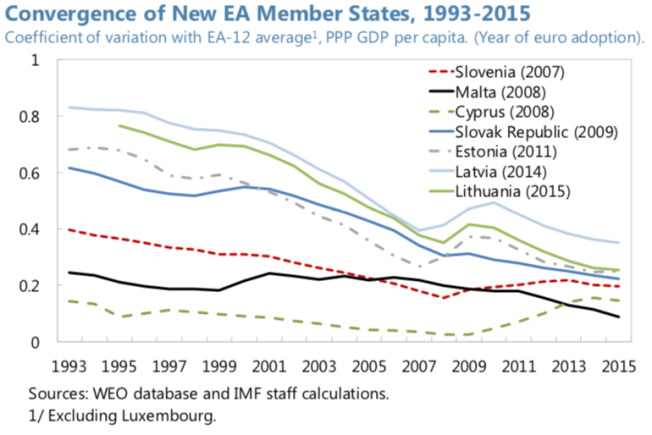

- „There was steady income convergence

across euro area countries in the decades

leading up to the Maastricht Treaty. (…) However, contrary to expectations, income convergence among EA-12 countries slowed after Maastricht and subsequently came to a halt.“

– Fazit: Klarer kann man nicht sagen, dass der Euro gescheitert ist. Es handelt sich hier nicht um ein Papier von Eurokritikern wie Hans-Werner Sinn, sondern um Wissenschaftler der IWF.

- Und es kommt noch schlimmer: „Productivity among the EA-12 diverged under the single currency. While productivity growth has slowed in recent decades throughout Europe, the decline was more pronounced in some countries than in others. Contrary to expectations, there was no productivity catch-up following the introduction of the euro. A decomposition of annual GDP per capita growth across countries with high and low initial productivity levels shows that countries use of factors of production more than offset the growth contribution of greater capital investment in these countries, forestalling real convergence. A larger fall in investment and employment since 2008 further added to the post-crisis divergence in economic growth.“

– Fazit: Also auch hier ist der Euro gescheitert.

Quelle: IMF

Business Cycle Synchronization

- „(…) business cycles were already highly

synchronized across euro area

countries in the three decades leading

up to the euro in 1999. From 1999

to 2007, business cycle

synchronization increased further, followed by an additional sharp increase in the post-2008 period. The increase in concordance was broad-based. Germany in particular has experienced increasing synchronization over time, and is the country with the highest degree of synchronization post crisis.“

– Fazit: was zumindest aus deutscher Sicht nicht nur positiv ist. Als Exportland wäre es besser, unsere Kunden würden zu unterschiedlichen Zeiten boomen oder in der Rezession stecken. - „However, after some initial narrowing, the amplitude of business cycles has diverged. (…) While the high degree of cyclical synchronization ensures that the common monetary policy points in the right direction for most EMU member states, the divergence in amplitude means that the optimal degree of tightening or loosening of macroeconomic policies would differ for different countries.“

– Fazit: also auch hier keine wirklich gute Nachricht. Die Ökonomen haben keinen einzigen wirklichen Vorschlag, um die Synchronisation zu verbessern, als für mehr Umverteilung zu werben. Dabei könnte man über Bildungsstandards und Investitionen in die Zukunft nachdenken.

Financial Cycle Synchronization and Capital Flows

- „In contrast with business cycles, the degree of financial cycle synchronicity fell in the initial phase of the euro, but then rose in the wake of the crisis. A euro area financial cycle upswing started around the time of the euro introduction and lasted until the financial crisis. The downturn started with the crisis in 2009 and lasted through the end of the estimation period. (…) While the overall degree of financial cycle synchronization was similar to that of business cycles, bilateral financial cycle concordance numbers varied much more widely than those of business cycles, indicating greater dispersion among countries.“

– Fazit: was auch damit zu tun hat, dass die Risiken von den Marktteilnehmern prozyklisch gesehen werden. - „Germany’s financial cycle has become increasingly disconnected from the others. (…) This disconnect reflects

Germany’s distinctive credit and house

price dynamics, which differ from those

of most EA-12 countries. Credit to the

private non-financial sector remained flat

between 2004 and 2011, preventing a

subsequent private debt overhang and credit supply contraction. Similarly, Germany’s house prices remained stable until 2009 and grew relatively slowly thereafter. The relatively low home ownership rate in Germany may also have played a role.“

– Fazit: Lassen Sie mich das übersetzen: Weil es bei uns keinen Schuldenboom gegeben hat, sind wir weniger mit den anderen „synchron“. Ist das wirklich ein Nachteil für den Euro? Wohl kaum, denn so kann unsere Politik denken, „wir wären reich“ und zur Rettung eilen. - „Our analysis shows a large and growing variation in amplitudes across national financial cycles. In particular, financial cycles were strongly amplified in Spain, Ireland, and Greece, with standard deviations close to five times the euro area average. These countries experienced financial cycles of increasing duration and magnitude after euro introduction, in sharp contrast to core euro area countries, as cross-border bank flows from core country banks to the private (Spain, Ireland) and public (Greece) sectors boomed.“

– Fazit: Da hat der Euro als ein Schuldenturbo funktioniert. Gut?

Adjustment Mechanisms in the Euro Area

- „Cross-country flows in labor, capital, goods, and services markets were expected to help income convergence and countries’ capacity to adjust to shocks in the single currency. In the face of common cyclical shocks, it was envisaged that fiscal policies would work with the common monetary policy to dampen the business cycle.“

– Fazit: Also sollten Staatsausgaben helfen, um Schocks abzufedern. Dabei wissen wir, dass es eben nicht genügt. - However, the envisaged adjustment mechanisms under monetary union have been insufficient to support convergence, and have in some cases contributed to divergence. Labor mobility remained modest and trade integration was less than expected. Countries did not advance structural reforms as expected, and fiscal policy in practice often was procyclical rather than countercyclical. Capital flows did boom spectacular in the early years of monetary union, but they proved destabilizing rather than shock absorbing, as demonstrated by the sharp reversal of capital flows during the crisis. Moreover these capital flows did not generate convergence of productivity to produce sustained real income convergence. ECB research suggests that some 80 percent of income risks remain unsmoothed through fiscal, price, credit, and capital flow channels and that the degree of risk-sharing has actually fallen in recent years.“

– Fazit: Offensichtlich müsste man doch hier anpacken, wenn man die Eurozone stabiler machen will. Mehr staatliche Umverteilung ist aber nicht die Antwort. Die Frage wäre doch, wie man private Kapitalströme mehr motiviert (Reformen, Eigentumsschutz) und zugleich eine Fehlallokation in unproduktive Sektoren verhindert. - „Intra-euro area trade is substantial, but has not increased as much as predicted. Contrary to expectations., there is little evidence that EMU has stimulated trade. Intra-euro area trade increased less than trade with non-euro area countries.“

– Fazit: ein wichtiges Thema, will man die Eurozone stabilisieren.

- „The adjustment impact from intra-EU labor mobility has also been modest. (…) In fact, most of the recent rise in intra-EU mobility is due to East-West flows following EU enlargement, as can be seen by the increase in EU-28 flows.“

– Fazit: Auch hier fehlt damit ein wichtiger Schockabsorber. - „Capital flows, meanwhile, increased substantially, but financed investments in low- productivity sectors and drove unsustainable booms. The elimination of currency risk and the lowering of interest rates boosted intra-euro area capital flows, with cross-border claims in euros of euro area banks rising from below €1 trillion in 1998 to close to €10 trillion at the peak in 2008. (…) Banks concentrated their new lending in sectors with low productivity, especially housing, construction and other real estate activities, fueling housing price bubbles in Spain and Ireland, increasing risks to financial stability. When the euro area crisis hit in 2010, capital flows were reversed, forcing rapid adjustment.“

– Fazit: Tja, Banken finanzieren nun mal nichts lieber als Immobilien. Da müsste man ansetzen. Jedoch, kein Wort dazu in dem Papier der Ökonomen aus Deutschland und Frankreich.

- „EMU membership did not generate structural reforms beyond what was observed in other advanced economies. (…) Labor tax policies diverged in the first ten years of EMU, which set different incentives for employment across countries and influenced their potential growth. The dispersion of labor tax wedges increased significantly with the introduction of the euro in 1999.“

– Fazit: Natürlich braucht man keine Reformen, wenn die Wirtschaft dank des billigen Geldes boomt. - „Widening competitiveness gaps led to the buildup of external imbalances within the euro area. In many countries, wage growth outpaced productivity growth, contributing to a build-up of competitiveness gaps (text chart), as manifest in persistent inflation differentials and divergent real effective exchange rates. More competitive economies such as Germany experienced widening current account surpluses, while countries with weaker productivity growth and higher inflation such as Spain saw widening deficits. Limited labor market flexibility compounded the competitiveness problem and increased the burden of adjustment following the crisis.“

– Fazit: Die Charts dazu habe ich schon in meinem Büchlein „Die Krise … ist …“ gezeigt. Es war einfach nur eine Party. - „Capital flow-driven boom-bust dynamics ultimately contributed to imbalances and real economic divergence. By supplying exuberant investment in low-productivity sectors, pre- crisis capital flows exacerbated economic

disequilibria in the form of misalignments

between productivity and compensation, which

undermined incentives for efficient resource

allocation and sustainable growth. The

retrenchment of cross-border bank lending

further weakened periphery banks’ balance

sheets and reinforced the credit crunch,

hindering the reallocation of labor and capital.

In hindsight, the financial imbalances linked to

the different positions of countries’ financial cycles created unsustainable booms and large current account imbalances (text chart), encouraged pro-cyclical fiscal policy in recipient countries, and contributed to resource misallocation, thereby lowering potential output.“

– Fazit: eine gute und klare Zusammenfassung. Selbst, wenn wir alle Reformen, die von den Ökonomen vorgeschlagen wurden, umsetzen würden, könnte sich genau diese Entwicklung wiederholen. Nichts wäre also gewonnen.

- „Finally, fiscal policy tended to exacerbate the cycles. The Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was meant to prevent national fiscal policies from producing negative spillovers on other countries and on the conduct of monetary policy. However, the SGP framework did not fully prevent pro-cyclical fiscal policies before the crisis. In addition, compliance with the SGP rules was weak and the complexity of the framework has hampered effective monitoring.“

– Fazit: Auch hieran ändert sich bei realistischer Betrachtung nichts.

Was sollte getan werden?

- „Common fiscal mechanisms could play an important role in macroeconomic stabilization. (…) a central fiscal capacity would provide countries with more flexibility in responding to such asymmetric shocks, cushioning the impact of the required internal devaluation. It would permit a more accommodative fiscal stance in a downturn, while supporting fiscal discipline in good times.“

– Fazit: Dabei hat der IWF in einem anderen Papier vorgerechnet, dass dies gar nicht geht, weil die Größenordnungen unrealistisch sind. Vielmehr gilt es, den Privatsektor zu mobilisieren, um auf diese Weise mehr Ausgleich zu erreichen.→ IWF: „Toward A Fiscal Union for the Euro Area“, 25. September 2013 - „Expanded centrally-financed EU investment could raise potential growth in lagging countries (…) higher public infrastructure investment through mechanisms such as EFSI and structural funds could raise growth in the short term by boosting aggregate demand in a downturn and in the long term by increasing productive capacity.“

– Fazit: Ich wüsste nicht, wie noch mehr Autobahnen in Portugal dem Land helfen. Es liegt, was Innovationen betrifft, auf dem Niveau eines Entwicklungslandes. - „Greater efforts are needed to improve structural flexibility and close competitiveness gaps. Structural reforms would enhance countries’ capacity to adjust to shocks, but would also help improve productivity growth in lagging countries to strengthen competitiveness and ultimately foster income convergence (…).“

– Fazit: O. k. und wieso sollten jetzt die Reformen kommen, die schon die letzten 20 Jahre nicht gekommen sind? Aber immerhin werden sie hier noch gefordert. Die deutschen Ökonomen setzen mehr darauf, unser Einkommen zu transferieren. - „Sustainable income convergence would bolster the political stability of the monetary union. (…) Productivity growth requires greater capital investment, including in human capital, better allocated to growth ‑enhancing areas. Ultimately, greater income convergence can help strengthen both the support for the monetary union and strengthen countries’ resilience to shocks, thereby alleviating concerns about permanent transfers from richer to poorer countries.“

– Fazit: Hm, was meinen sie hier. Ich denke, auch mehr Umverteilung, damit die ärmeren Länder nicht so unzufrieden sind. Übrigens, die mit dem geringeren Einkommen sind dennoch reicher als wir, wenn man auf das Vermögen blickt. Nur zur Erinnerung.

→ IWF: „Economic Convergence in the Euro Area: Coming Together or Drifting Apart?“, 23. Januar 2018

Dr. Daniel Stelter — www.think-beyondtheobvious.com